For Beginners: What is capitalism? What does it mean to be ‘anti-capitalist’?

People throw around the word ‘capitalism’ a lot. But chances are, different people understand that word to mean lots of different things. Here I try to break down the basics of what I mean when I say ‘capitalism’, and why I think it’s time for a different economic system.

Capitalism: An Economic System Based On Exploitation

By ‘economic system’, I mean the system of deciding how things like housing, type of work, food and power (like the power that a parent has to make decisions over their child’s pocket money, the power that the police have to fine or exert force over people, or the power a boss has to sack you for no reason), are spread among different people. An economic system is the system by which money, resources, goods, and access to services are allocated to, or are open to, different people, based on their differing positions within society.

In a capitalist economic system, only a few people — referred to as the ‘capitalist class’, ‘ruling class’, ‘bourgeoisie’, the ‘1%’ — control the ‘means of production’.

By ‘means of production’, I mean all of the material things that are used in order to do work and make profit. This includes raw materials, machines, land, and more. This can be things like the photocopier in an office, the bricks and cranes on a building site, the coffee mugs at a cafe, and the heavy machinery used in mines — all of these things are the ‘means of production’ as all of them are used by people doing work, they are the means by which things are produced.

The majority of people are part of the ‘working class’ (which is sometimes called the ‘proletariat’) who do not own the means of production but instead have to sell their time and their effort — their ‘labour’ — to the capitalist class who do own the means of production. The means of production + the labour of workers creates profits for the capitalist class.

Exploitation: A Closer Look

The relationship outlined above between the capitalist class, the working class, and everything in between is necessarily exploitative. This relationship relies on exploitation to keep it in place. Why? Well, to put it very simplistically:

- If a worker in a factory creates goods or services that can be sold for more than [the amount of money paid to the worker for their labour] + [the amount the capitalist spends on the raw materials or the ‘means of production’ used], this generates a profit; a surplus amount of money.

- When that profit does not at all go to the workers but instead to someone else — the CEO, owner or shareholders, for instance — who didn’t do any of the work, that’s exploitation.

- It is the labour of the workers that enables profits to be generated, but these profits go to just a small number of people — who often did little or nothing to contribute to the creation of the goods and services being sold for profit — while workers have steady or even stagnating wages.

- The CEO, owner or shareholders who get to keep the profits will then have more money available to them, and be able to spend this on more factories, machines, raw materials, and hiring more workers. The CEO, quite commonly, can also spend this money on increasing their own wage, paying themselves and their management team bonuses, or employing more sophisticated accountants and consultants, who can reduce the cost of taxes, cut costs in employees or safety measures, cheaper resources, lower quality, marketing, etc.

- This in turn generates even more profit. Those who keep the profit will then be able to further invest, and so the cycle continues.

- The CEOs, owners and shareholders will accumulate ever-increasing levels of wealth, all the while the workers will likely be earning a steady, comparatively low, wage.

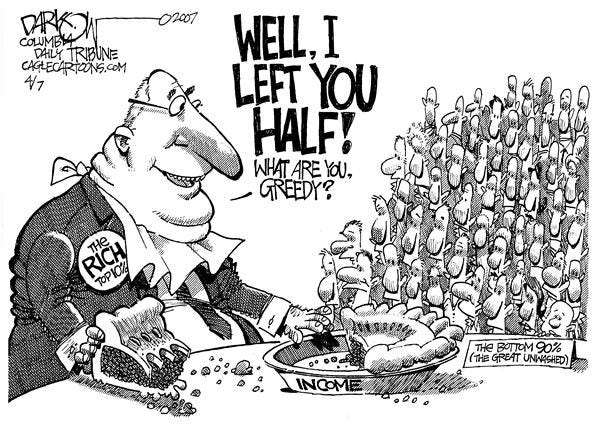

- This is exploitation: the CEO is exploiting the labour of workers in order to generate ever-increasing profits for themselves. We call this ever-increasing difference between the income and wealth of the 1% (the capitalist class) and the working class, the ‘wealth gap’.

- It is this cycle and process by which inequality inherently grows under capitalism.

Capital Accumulation

When money is being used in this way — being invested specifically in order to generate more money for the investor, as opposed to just being used by everyday people to buy food, spend on hobbies, pay rent, buy gifts for friends, for nights on the town, or to cover transport costs etc. — it is functioning as ‘capital’. When more and more money is functioning as capital, i.e, being used to expand or open more businesses or factories, this is called ‘capital accumulation’. Capital accumulation is what drives the expansion of the economy, which is presented under the capitalist system as a good thing, the be-all and end-all of economic success: think about how politicians brag about ‘tax cuts for business’ initiatives that will ‘expand the economy’ and thus create jobs.

Capital accumulation is maximised via increasing profits, which can be done through methods like decreasing wages for workers, reducing environmental protections, or cutting expensive ‘red tape’ around safe work conditions. A car factory that pays its workers minimum wage, doesn’t provide costly safety gear and doesn’t take into account or work to offset environmentally damaging work practices, will spend less money than a factory that pays its workers a living wage, provides a safe work environment and pays for more environmentally sound materials and processes.

However, both factories may produce a similar number and quality of cars, which may be sold for a similar amount. The factory that spends more money to get there will therefore generate less profit for its owner than the one that cuts corners on wages, conditions and environmental protections; the CEO with greater profits will then have a greater amount of capital to invest, accumulate further capital, grow the capitalist economy and be more “successful” than the CEO of the factory that attempts to provide slightly better pay, conditions and environmental protections. Eventually, the company with the CEO who pays more or introduces more environmental protections may go out of business due to competition, or be bought out by the more ruthless CEO.

Unemployment & Reserve Army Of Labour

Some argue that workers have a choice — that if they don’t like the pay and conditions they are receiving in their job then they should just find another. If this were indeed the case, then capitalism would work less effectively. If workers were to universally have the choice to simply take on work that has good pay and conditions, this would undercut profits for the capitalist class, lead to less capital accumulation, and less economic expansion. It is for this reason that the capitalist system requires a minimum level of unemployment in order to function successfully. The group of people who are perpetually in insecure and erratic employment are the ‘reserve army of labour’. These people may be hired when there is a need for labour, and fired when there is not.

In Australia as of 2017 there are approximately 18 jobseekers for every job that is available. In this climate of mass unemployment, workers are in no place to simply “get a better job” or ask for adequate pay and conditions. Workers are taught to be happy and grateful for any job they can get. The threat of becoming unemployed constantly hangs over workers’ heads, making them compliant, hard workers, and unwilling to fight for their rights — they know that the threat of them quitting or withdrawing their labour is no threat at all when there are thousands of other desperate people willing to do their job for the poor wages and conditions offered by their boss.

Strikes

This is where the ‘strike’ comes into things. A strike is when an organised group of workers — a group of workers in a union — all collectively refuse to work, in order to try to gain better pay or conditions. An individual refusing to work is generally ineffective as a method of protest: they will likely just get fired. When workers in an entire workplace or an entire industry refuse to work simultaneously, the capitalist class bosses are put in a difficult situation as they cannot simply fire everyone.

Entire workplaces or entire industries grind to a halt for the duration of an effective strike. Strikes temporarily stop the flow of profits to the capitalist class, clearly illustrating that it is the labour of the workers that generates profit, and giving the workers a position from which to bargain.

The more people who participate in a strike, the safer this tactic is, the less likely the boss is to fire or otherwise discipline striking workers, and the more likely the boss is to be pressured to give in to the demands of the workers.

This is why it is important to never ‘break a strike’ or ‘cross a picket line’ by going to work when the rest of the workers in the workplace are striking. When a worker refuses to participate in a strike, gives in to their boss and goes to work anyway, they are actively undercutting the strength of the bargaining position of the workers who are choosing to strike, and making the strike less effective and more risky. Those who cross picket lines or break strikes are sometimes referred to as ‘scabs’. This is not a slur: it is a descriptive word for someone who engages in ‘strikebreaking’ — lessening the bargaining power of their fellow workers by maintaining some of the profit flow to the bosses.

In most cases, increased pay and conditions won via strikes (important historical examples including winning the 8-hour workday, the 5-day work week, and child labour laws) do not just go to the people who took part in the strike but to all workers in the striking workplace or industry. This is why there is often animosity towards scabs who cross picket lines — if the strike is successful, these people will gain as much of the benefit of the strike as the workers who went on strike themselves, but without taking on any of the risk, and having actively chosen to make the strike more dangerous for striking workers.

The “Bootstraps” Myth

Now, you might think that if someone owns the means of production then they deserve to take the profits of the goods and services created, because it is ‘their’ buildings, materials, factories etc. that are being used by the workers to generate the goods and services that earn them profits. I disagree. In order to own the means of production, one must have capital to invest in the first place. Under a capitalist system in which most people have to sell their labour to earn a wage to survive, and while inequality is at such high levels that workers’ wages are a lot lower than the profits generated and taken by the capitalist class, proportionally very few people will ever be able to earn and save enough money that they will be able to purchase things like machines, buildings and raw materials.

Most of the people who own the means of production were born into wealth, or otherwise very lucky. If one could simply choose to work differently and become a member of the capitalist class, wouldn’t everyone do it? The idea that one should simply ‘pull oneself up by the bootstraps’ is very much a myth under this rigged and vastly unequal system. Sure, the cases in which people really do come from rags to riches, start their own businesses and become wildly rich and successful, are widely talked about and promoted. However, that doesn’t make them the norm, or even possible — let alone likely — for most people; cases in which this happens are very rare and invariably a result of luck. The few workers who do achieve upward mobility may well be very hard workers. However, a far greater number of workers work extremely hard and never achieve this type of mobility.

It is beneficial to the capitalist class that ‘rags to riches’ stories are spread, because these stories make workers think that if they work hard enough under this economic system, anyone can advance their economic standing by generating profits for themselves rather than continuing to be exploited. When workers work harder, the capitalist class then can extract even more profit from their work. The means of production continue to be owned and amassed by fewer, richer, people, while the income and wealth disparity between workers and the capitalist class continues to rise. Belief in the possibility for upwards class mobility can also hold workers back from thinking about or working towards different economic systems that are less exploitative.

Beyond the issue of exploitation, the capitalist system roughly outlined up to here has countless other pitfalls, including its capacity to stifle democracy, galvanise war and conflict, and impact horrendously on our climate — I will write about this further if I get around to it!

Consider: Capitalism Is Not ‘Broken’ — It’s Working Exactly How It’s Meant To!

I’ve heard it said lots that the problems we’re seeing in the world as a result of the capitalist economic system show that ‘capitalism is broken’ and we should look to reform it to make it work better. Some say it is just ‘neoliberal’ capitalism that is the problem, or ‘crony’ capitalism, or it’s just that we have a ‘corporatocracy’ — where government and business are one — and if we just got rid of ‘corporatism’ we’d be fine. I disagree. Skyrocketing inequality isn’t a sign that capitalism is broken, it’s a sign that it’s functioning how it is designed to function. The capital accumulation model at the heart of the capitalist system as outlined above actively relies on the existence and maintenance of a capitalist class and a working class, and inherently results in increasing the concentration of capital in the hands of the very few. It relies on selling the Bootstraps Myth to the working class through the media and marketing, and making sure that any deviation from this model — such as strike action, protesting and union organising — is criminalised and controlled through the police and legislation.

We’re seeing this play out in the real world right now — in 2010 the wealthiest 388 people in the world owned as much wealth as the bottom half of the world population; by 2016 this number has reduced to 8 people. The fact that fewer than 8 individuals hold as much wealth as the bottom half of the world’s population is not a sign that capitalism is broken, it’s a result of the inherent, core processes of the system itself.

Similarly, climate devastation caused by mass industrial expansion isn’t a sign that capitalism is broken, it’s an unavoidable feature of how capital accumulation — success under the capitalist economy — works most effectively. Capitalism is working just fine, it is simply not a system that benefits the majority of people or the planet.

Alternatives To Capitalism — A Better System

Now, you might be thinking ‘sure, okay, you don’t like capitalism…but it’s all we’ve got at the moment, what’s your alternative?’

Well, there are loads of different ideas about what a different economy could look like, and I don’t claim to have all the answers or a blueprint for the perfect economic system all set up and ready to go. But on a base level, I’d like to see an economic system in which the means of production are not owned by a capitalist class made up of proportionally very, very few people, who generate massive profits from the labour of the much larger working class. I’d prefer to see an economic system in which decision-making and power in workplaces is decentralised and democratic, and the means of production are owned by the workers themselves. Imagine: a factory or workshop where all the workers there equally own the equipment being used, and equally share in the profits their work generated. If we take away the hegemonic power of the ruling class, we open a world of possibility and incentive for things like shorter work hours, universal education, housing and healthcare, and industrial practices that benefit rather than harm the environment.

Some might suggest that this is still a bit extreme and that we should just focus on ‘reforming’ capitalism rather than building a new economic system altogether. But reform of a system whose core principle is the accumulation of capital, rather than the benefit of people or the environment, will never be enough. Why would we want to cling on to a system whose primary requisite for success — capital accumulation — actively and necessarily harms people and the planet? Tinkering around the edges or trying to avoid the worst implications of capitalism is at best a disappointing half-measure and at worst a destructive drain on left-wing energy and prolonging of an incredibly dangerous system.

The idea of ‘overthrowing capitalism’ sounds violent and scary to a lot of people, because of the media frenzy that is whipped up by the capitalist class when anyone questions the dominant economic system. It shouldn’t be radical to suggest that people should not have the value of their work taken from them, or that workers could collectively own the means of production rather than accepting that a very few people are somehow entitled to excessive wealth. In reality, being anti-capitalist means to me that I recognise capitalism as exploitative, and see that there are other ways in which we could order our economy that would be fairer and less harmful.